Written by Harriet Maher

January 9, 2023

There is a well-known book on modern art called “Why Your Five Year Old Could Not Have Done That.” It speaks to the once-common dismissals of abstract and ‘primitive’ styles of art as childish; art that we now prize above any other genre. But perhaps the next criticism we could be hearing in contemporary art circles is “my robot could have done that.

Sophia the Robot, Self Portrait, 2021

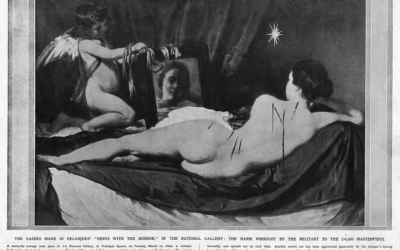

AI-generated art is making its way onto the world stage and into the mainstream, and with it comes a serious revision of what art is, and what it could be. To put it in a sentence that I never thought would be possible to write, Sophia the Robot has released a collection of NFTs on this month. The images represent the AI’s interpretation of a female-centric ‘herstory’ of art. And if that seems too niche to have any real bearing on the future of art, the curator of the 2022 Venice Biennale, Cecilia Alemani, has revealed that one of the key precepts for this year’s festival is “the idea of overcoming the centrality of man and then becoming earth, becoming machine, becoming nature.”

If indeed we are ‘becoming machines’, and if machines can harness cumulative knowledge to produce new and creative works of art, and if these works of art are indistinguishable from works made by human hands[1], what does this mean for the future of art? If we think of creativity as the last stalwart of humanity, and this is now able to be imitated by robots, how do we think about the definition of art and the role of humanity in an ever-more automated world?

AICAN, Permutations, 2021

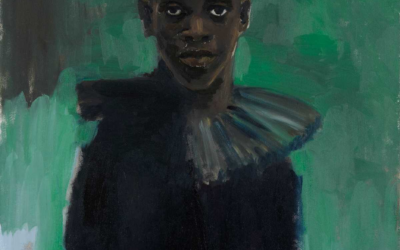

We tend to think about creativity and the artistic impulse as abstract, innately human concepts that stem from our lived experiences and physical embodiment. But some AI researchers disagree. These scientists look at creativity as “something that can be investigated, simulated and harnessed for the good of society.”[2] Indeed, this is what is being undertaken at some research labs across the world, and the results are either impressive or alarming, depending on your perspective. AICAN (Artificial Intelligence Creative Adversarial Network) was developed by Dr Ahmed Elgammal at the Art and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory at Rutgers University. The program has been trained to learn from art history in order to produce algorithmically new and creative pieces. Permutations is from the first collection ever created by AICAN, and the piece is now available as a single edition NFT on digital art marketplace SuperRare The work itself is painterly, abstract, and uses colour in a way that draws the eye to the dark, receding centre of the image. In a word, it is captivating. But the argument that AI could eventually replace human creativity begins to fall apart when we remember that AICAN is only able to create new and unique pieces of art because of its education in art history. The technology was fed 80,000 of the greatest works in Western art history (which is in itself a subjective and contentious statement). The idea was for AICAN to study these works, and to comprehend the smallest brushstrokes, colour usage and depth of field used by the artists. Although AICAN is programmed not to imitate existing styles, there would be no capacity for its own creativity without the precedent of human artistic output. The machine cannot learn what doesn’t already exist in the world – which, at this point in the technological revolution, has been created by hands of flesh and bone.

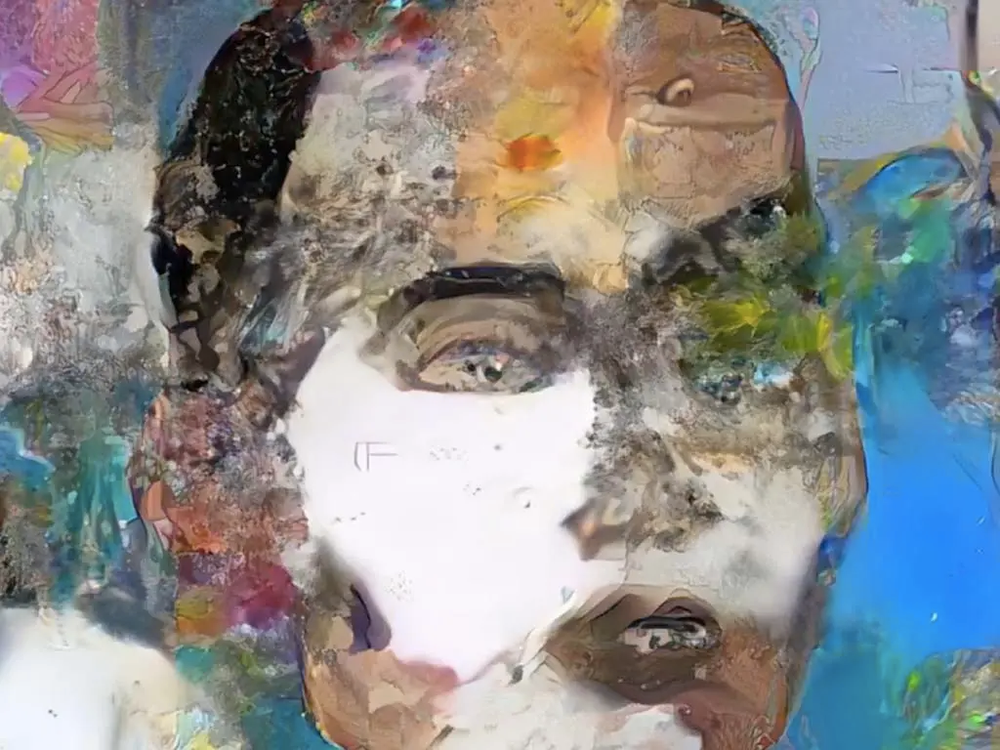

The delicate tension between human knowledge, creativity, and AI, is beautifully illustrated in artist Sarah Meyohas’s 2017 work Cloud of Petals. The project spans film, digital works, cryptocurrency and NFTs across five years; making it a tour de force that blurs the lines between human and machine. In some ways, it is a move towards realising Donna Haraway’s visionary Cyborg Manifesto, presciently published in 1985. For Meyohas’s work, she commandeered the former site of Bell Labs, where sixteen workers photographed 100,000 individual rose petals. From each rose, they selected the petal they thought was the most beautiful, and this single petal was pressed and preserved. The massive dataset compiled with the photographs was used to map out an artificial intelligence algorithm that learned to generate new, unique petals into perpetuity.[3] Like AICAN, the AI of Meyohas’s creation can only make its own aesthetic decisions based on human intelligence. Also like Elgammal’s programme, the AI is limited to a selective dossier of precedents. In AICAN’s case, it learned from Western art history, which is largely dominated by heterosexual, cisgender, European men. In Meyohas’s work, all sixteen workers selecting the rose petals were men. What Meyohas’s project attempts to discover is whether taste or aesthetic judgement can be taught and learned, or whether it is an intrinsic human trait.

Sarah Meyohas, Cloud of Petals, 2017

In the case of AICAN, Sophia the Robot, and the AI in Cloud of Petals, the programs’ creativity is based solely upon human precedents. The AI demonstrates an ability to study and understand existing art, and to somehow distil or interpret it to produce something new. There is a strong feeling amongst art lovers (myself included) that machines cannot produce art in any meaningful sense, because they lack this inherent, inexplicable sensitivity. But when I scroll through the AI-generated petals of Meyohas’s project, I feel a sense of awe that a machine, devoid of sentiment and the embodied experience of nature, could craft and produce such delicate, subtle, and beautiful things.

As our phones become more like hands and Elon Musk’s dream of inserting microchips into our brains becomes a more likely reality every day, some artists are embracing the ability to become cyborg-like, in order to overcome previously restrictive physical barriers. Nathan Copeland was paralysed from the chest down in 2004 following a life-changing car accident. In 2015, he became a participant in a brain-computer interface (BCI) study at the University of Pittsburgh. Copeland had four micro-electro arrays implanted in his motor and sensory cortexes, which translated his brain signals into commands and then relayed those commands to a device. For Copeland, this device was a robotic arm, which he could subsequently control with the power of his thoughts. Drawing was an obvious exercise for Copeland to test his skill and enhance his dexterity, so he began to do so in earnest using a basic computer software program. He has now sold over $13,600 worth (at the time of writing) of NFTs on platform OpenSea. Although this is not the same as AI, the BCI used to make Copeland’s drawings possible harks back to the notion of the interchangeability of machine and human that is currently experiencing a moment of rapid growth.

Nathan Copeland, You Are Loved, 2022

Artists have always been at the frontier of culture, and have shaped how we share and connect through art. Reflecting on Cloud of Petals, Samuel Loncar notes that “art, like fashion, seems future-oriented, breathless in its pursuit of felt relevance, looking for the next big thing.” This impetus explains the current furore around AI art, NFTs and the digitisation and gamification of art. So could the ‘next big thing’ be, in fact, art that is devoid of human interference, art that is purely generative? In a word, no. While the developments that have been made in AI, BCI, and blockchain technology are indeed significant and thrilling, there is still, even within these spheres, a drive towards community and connection. We can certainly admire Sophia the Robot’s interpretation of female-centric history, and Copeland’s incredible work with BCI to produce nostalgic, vivid scenes reminiscent of early animation and video games. But most of us like our art with a smudge of the abject. We want to see bodies touching, to feel a jolt of desire or an awakening, a moment of recognition. Humans can benefit from the integration of AI and technology, but the relationship is mutual.

Need a writer for your website, newsletter or social media?

[1] Sarah Cascone, ‘AI-Generated Art Now Looks More Convincingly Human Than Work at Art Basel, Study Says’, ARTNews July 11 2017. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/rutgers-artificial-intelligence-art-1019066 . Accessed Feb 17 2022n[2] Ramón López de Mántaras, ‘Artificial Intelligene and the Arts: Towards Computational Creativity.’ The Next Step: Exponential Life, BBVA, 2017n[3] https://sarahmeyohas.com/cloud-of-petals

Related Articles

Weekend Viewing: 13-15 January

It's a new year and there is a brand new lineup of shows opening around the world . Here are some of my top picks for exhibitions to check out this weekend, both online and in person. From biennials to blockbusters and everything in between, this short list will...

Just Stop.

Why using art as a vehicle for protest isn't the solution There’s been a lot of art in the news lately, but not necessarily for the right reasons. We’re used to seeing Picasso, Van Gogh and Munch’s names splashed across the pages of newspapers and the internet, but...

Weekend Viewing: 25-27 November

It's Black Friday, and that means hunting for deals! But if you (or your debit card) need a break from spending, here are some of my top picks for exhibitions and shows to check out this weekend, both online and in person. From biennials to blockbusters and everything...